The Simplest, Best Bible Curriculum for Homeschool Families

Parents are always asking for recommendations about the best curriculum options for everything. For instance, “what is the best homeschool Bible curriculum?” I tend to think that we unnecessarily overcomplicate most things. You’ll find that “keep it simple” is a pretty common theme with me, and this is no exception. As far as I’m concerned, the best Bible curriculum for homeschool families is, in most cases and/or for the most part, not really a “Bible curriculum” at all.

What’s the Goal?

What is the goal of a Bible curriculum? To know Scripture and to know how to use Scripture, right? And how do we do that in the real world?

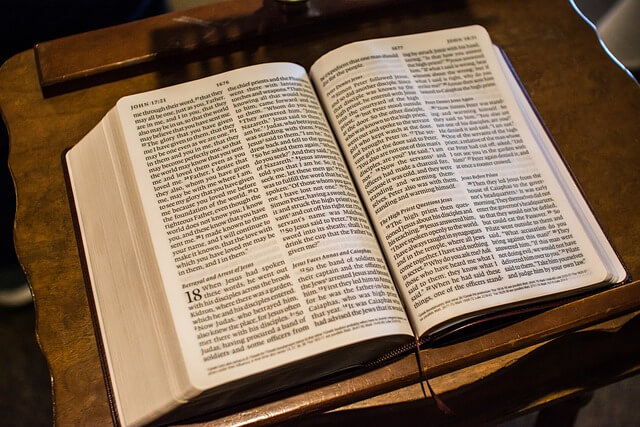

We read it.

Ideally, we also have some guidance in learning to read it well, and we might use study tools, but fundamentally, we get to know it by reading it.

You can “do Bible” pretty simply, without conventional or complicated curriculum, by keeping to the same basic principles. Read the Scripture with your children. Teach them to read it. Help them learn to use study tools. And, yes, we use a handful of resources for this, but we don’t use a “Bible curriculum” to accomplish it.

Read Scripture with Them

The most basic foundation of teaching our children Scripture is simply to read it to them and with them. Family worship exposes them to the Word, teaches them that it’s a priority, and begins to give them a general familiarity.

There are 1,189 chapters in the Bible. If you read a single chapter together every day starting at birth (and assuming no overlap), by the time your child turns 18, he will have heard the entire Bible five times — not counting any additional reading.

Of course, it’s also important to also teach the kids to read when they’re developmentally ready, so they can begin to read on their own. We’ve actually found that ours are motivated by our family worship times to develop this skill, because they want to be able to read with everyone else!

I recommend not “dumbing it down” with children’s versions, but allowing them to stretch and grow into the ability to read and understand the full translation older family members use, because a full, quality translation will be necessary for study.

Use a Catechism

Although a catechism isn’t essential, a simple children’s catechism can help give children a theological framework that makes it easier for them see the structure of the whole. The God With Us children’s story Bible also does a fantastic job of providing this overarching “big picture.”

Even if you don’t formally study the questions and answers, just playing the catechism set to music is beneficial. (We also like to play a lot of Scripture music, which further provides a general familiarity to kids with a variety of passages.)

Develop a Reading Habit

Having a personal “quiet time” is an important Christian life skill — and one that kids can begin practicing as soon as they can read fluently. You can start with a really straightforward option like giving them a basic checklist of chapters in the Bible and letting them just read a chapter (or more, as they prefer) per day, and check them off as they finish them.

This has the advantage of being incredibly simple — but it’s also a lot of chapters, and many of those can be tough to wade through one after the other.

Or, alternatively, Greg Lanier’s “Redemptive-Historical Bible Reading Plan” can be an excellent first reading plan. It doesn’t cover the entirety of the Bible; it’s selective, so it’s less likely to, say, bog your kids down in a zillion chapters of census-taking in Numbers. But it’s carefully selective so as to give readers the overarching story of Scripture.

And then, when they’re more comfortable and less easily overwhelmed, they can move on to an every-chapter-of-the-Bible plan.

Help Them Use Tools

As they get a little older, you’ll probably want to introduce your kids to Bible reference tools. You teach them to use conventional reference tools like dictionaries & encyclopedias; teach them to use biblical reference tools, as well.

The most significant of these is likely to be a Bible concordance. Other common resources include Bible dictionaries (kind of like concordances, but more extensive with their explanations), commentaries, and “cultural” references like maps and “manners and customs” references.

I like to teach the kids to use a printed concordance, so they have the ability (just as I teach them to use a “real” dictionary, in case the digital version should ever be unavailable for whatever reason), but we primarily use Bible software that includes most of these reference materials as well as the ability to compare translations. (Our worldview questions provide a great opportunity to teach use of a concordance if the kids aren’t already familiar with it by then.)

Teach Them to Study

There are a couple of key pieces to solid study: the process and…what I suppose we can call the presuppositions.

The process is the steps you take when studying a verse or passage. Inductive study is generally the most broadly-applicable and reliable. It’s comprised of three steps:

- Observation. What does the text actually say? This is typically your who, what, when, and where, and maybe how. If (to really simplify things) we had a verse that said, “Jesus went to Galilee,” we’d have several pieces of information here. Who? Jesus. What? “went.” Where? To Galilee. There isn’t a lot of “figuring out” here; you’re just noticing what’s plainly there in the text.

- Interpretation. What does the text mean? Now you’re getting into more of that “figuring out.” You might be discovering the why, and/or more of the how. In some cases, you might be inferring more details. For instance, in Luke 4, we read about Jesus healing Simon’s mother-in-law. We can infer from this that Simon had a wife, even though the text doesn’t specifically tell us that he was married. By comparing other passages, we can also determine that this “Simon” was, in fact, the apostle also known as “Peter.”

- Application. What does the text mean for me? Now that I know what the text says, and what it means by what it says, how do I apply it in my life? What do I do with it?

This is a pretty simple process, but it’s easier or less easy depending on the passage. Very straightforward passages like narrative passages or those with very clear instructions to the church might be pretty easy to understand. Others, like certain prophecies, are more difficult. But the same process can be used over and over for any passage of Scripture.

We really like the book Learn to Study the Bible, by Andy Deane, because it does a solid job of teaching this in an accessible way — and it also teaches much of the second piece I mentioned: the presuppositions.

What I mean by this, in this context, is the background attitudes and understanding that you bring to the process. For instance, how different genres within the Bible are different and require slightly different approaches. We don’t expect poetry to be as literal as narratives, right? So the way we read poetry in Scripture and the way we read narratives in Scripture are a little different. Just as one example.

Likewise, we bring certain kinds of logic to our reading — or we should. One principle, for instance, is that a certain passage of Scripture “can’t mean what it never meant.” In other words, we can’t just make up something that makes sense to us in our modern world, that would not have made sense to the original audience, and decide that’s what the passage means. That’s anachronistic. We have to think about what the text would have meant to the people it was originally written to, or we’re likely to flub it up.

Deane covers a lot of these principles, and he does it little by little as it makes sense to the context. For example, he doesn’t talk about the genre of poetry until he’s actually talking about studying poetry.

It’s Enough

There can be a tendency to feel like this is “not enough,” but I promise you, it is. Having a familiarity with all of Scripture, not just parts and pieces of it, and being able to read it and read it well are important foundations — foundations which the majority of Christians are lacking. Although specific Bible studies can be useful tools, a heavy reliance on them often displaces these fundamentals.

Trust that the Word, well-read and well-studied, is enough.